Recently, I bought a copy of the book Spots by Judy Brummer. When I went to pick up a copy, Judy graciously lead me into her beach bungalow themed home and excitedly told me, "this book came about because of YOU and a lesson you gave in Relief Society (Church) on Journal writing! Do you remember? (The lesson was 10-13 years previous). She autographed my book,"February 2014 1st Edition

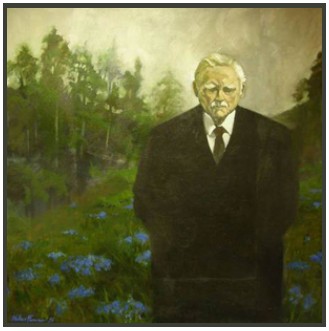

Arthur Henry King on Journal Writing

Today in my Family History Class we talked about Journals and personal record keeping. I read a chapter once in a book by Arthur Henry King that profoundly influenced what and how I write. I shared this advice today with my class members. Here are some of his thoughts on the subject:

The important thing to remember when writing a personal history or keeping a journal is that our descendants will be interested in the kinds of things that most interest us in the personal histories or journals of others. What kinds of things are these? First of all, the details of everyday life–details like our kitchen procedures and the way we treat our young children–because these things change so very much over the years. We are writing for posterity, and that posterity may extend for hundreds of years, and we can be sure that in one or two hundred years’ time those details will be very different indeed. Our descendants will also be interested in the fundamental things–the truly fundamental things–birth, death, and marriage. So we also need to leave them true accounts of the most important things that happen to us.

Our descendants will want to know what seems old and ridiculous to us, what seems new and interesting, what surprises us, what distresses us, what bores us, but above all, what interests us. They will want to know about our reactions to events, people, situations.

Our descendants will be interested in our genuine reactions, opinions, and feelings, not our conventional ones. . . When we write we need to be ourselves. We should not be misled by any teaching or cultural message we have received about being artificially cheerful or artificially anything. And we should not dismiss unpleasant matters from our minds. They must be faced, and our own responsibility for them must be assessed. Our responsibility is to tell the truth. We may need to reflect on how to put it down, but we should never reflect on how it will strike others, including our descendants. It is not for us to judge what we think will be good for them to read and what we think will not be good for them to read. The ways of salvation are not the ways of persuasion, but the ways of conviction. If we try to be truthful (and this is one of the few things we should try to be), then we are likely to convince. If we try to convince, we are less likely to be truthful. It is for us to set down the truth as we know it and think it; and for our descendants, not for us, to judge. Humility and honesty are two names for the same thing in writing. Try, therefore, humbly and honestly to assess your experience. Don’t try to make your experiences into more or less than they were, and above all, don’t think of your audience and try to appeal to them.

We need to keep in mind in writing, the style in which Joseph Smith presented his own experiences. His manner is matter-of-fact and cool. He doesn’t try to persuade us or work up out feelings. He may make us feel as a result of what he tells us, but he doesn’t make an effort to make us feel. He does not attempt to do other than describe what happened, including how he felt. There is an important difference between expressing one’s feelings and describing one’s feelings. When we attempt to express our feelings, we nearly always find ourselves, instead, expressing the feelings we ought to have had or should like to have had or exaggerating the feelings that we really did have. The attempt is enough to cancel out our chance of success. But if we try simply to describe our feelings we don’t fall into these errors.

Abstract statements about our feelings are boring and don’t really communicate. But a plain account may communicate a great deal. If we write down faithfully what happens to us, our feelings will come through, and they will be felt indirectly and therefore truly. So rather than say how we felt on our marriage day, we should try to describe what happened to us on that marriage day. Our feelings will come through much better than if we just say how we felt. We are more likely to be able to convey to our descendants something of what we really were if we try to set down the truth about what happens to us, and the more concrete and more detailed it is the better, and the less abstract it is the better. It is a mark of genius to single out the little details that make everything come alive; and very often that happens, not because one seeks to do it, but because one is in the right frame of mind and has taken one’s experience in the right way. Notice in the Joseph Smith story details like his leaning up against the mantlepiece when he gets home and the humorous remark he makes to his mother on that occasion.

. . . . A personal history always needs to be revised, because what we think is most important in our lives changes as our lives go on. Certain experiences become less important, more profound. Were we here simply to have certain experiences , life would soon be over for us. But we are here to live so that those experiences–for example the experience of temple marriage–may broaden and deepen and become richer as we grow older. Though we may think we understand the significance of eternal marriage, at the time we are married, we may understand it much more deeply later. In fact, we may spend a lifetime realizing or beginning to realize what the real significance of an eternal marriage is. So just as we should go back constantly to the scriptures and to other great books, we should go back to the most important experiences of our lives. . . . The greatest experiences of our lives need to be remembered and cultivated and thought of day after day. We don’t want to tuck them underground. They are there for us to keep, treasure, observe, know and live with. . . . The most important experiences of our lives shape our lives–they are our lives.

http://mormonscholarstestify.org/3164/arthur-henry-king